Supply Chain Structure – Classification | Strategies | Models

- Other Laws|Blog|

- 12 Min Read

- By Taxmann

- |

- Last Updated on 23 April, 2025

Supply Chain Structure refers to the strategic arrangement and configuration of all entities, processes, and resources involved in the flow of goods, services, information, and finances from suppliers to end customers. It defines how suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, distribution centers, logistics providers, and retailers are interconnected to deliver products efficiently and effectively.

Table of Contents

- Classification of Supply Chain Structure – Efficiency vs. Responsiveness

- Efficiency vs. Responsiveness

- Boundary for Efficient and Responsive Supply Chain

- Push-Based Supply Chain

- Key Conditions Enabling Push-Based Supply Chain

Check out Taxmann's Supply Chain Management which offers an in-depth exploration of supply chain management's strategic, tactical, and operational aspects, emphasising how businesses can secure competitive advantages through effective design and planning. Authored by Prof. N. Chandrasekaran, it seamlessly combines theoretical foundations with illustrations drawn from India, Asia, and beyond. Each chapter interlaces learning objectives, practice-oriented examples, and case studies on digitalisation, sustainability, and Industry 4.0. The concluding chapters cover advanced themes—such as supply chain finance, performance measurement, and organisational frameworks—making this resource essential for students, professionals, and researchers.

1. Classification of Supply Chain Structure – Efficiency vs. Responsiveness

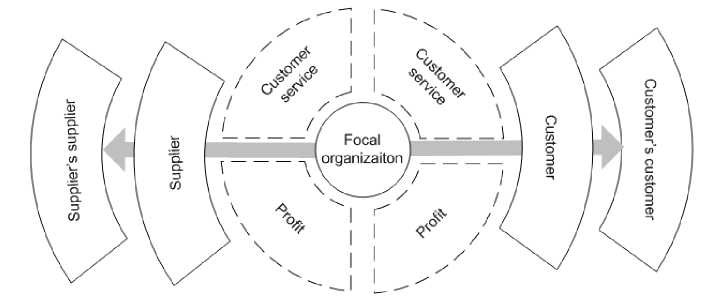

The structure of a supply chain network refers to the pattern or manner in which constituent parts are arranged together. The characteristics of such a supply chain network anchored by the focal organisation that exercises strategic influence on the nature of competitive forces, including sharing of profit across the supply chain constituents and level of customer service within the network, are referred to as structural factors. Those characteristics play an essential role in the conduct and performance of organisations participating in the supply chain network and provide a competitive advantage to the focal organisation.

In this mindset, the above would immediately reflect on the network of organisations in the supply chain. That would mean in terms of focal organisation’s supplier, supplier’s supplier, intermediaries logistics service providers, customer, customer’s customer, and so on. This is the correct approach. The design of a supply chain must consider such issues as WHERE and HOW the products are produced, and then ENTER the Market, where they are STORED, and how they reach a customer. Even this approach is manufacturing-centric and not supply chain-centric, i.e., customer-centric.

One key aspect being stressed throughout is setting the supply chain from the customer’s perspective, as the whole link serves a customer.

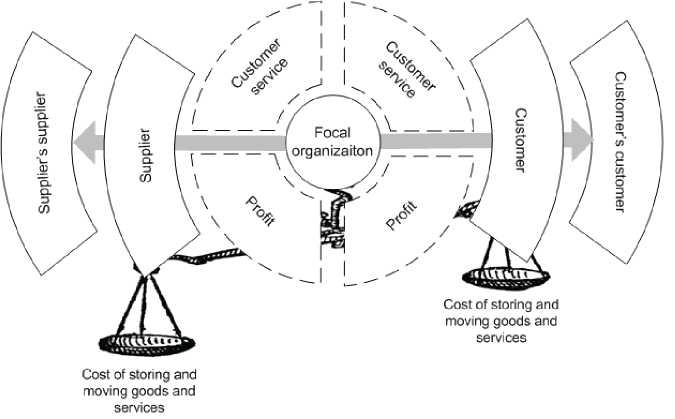

The structure is not all that! Most of these are discussed across various perspectives of this book and in any supply chain as an evolutionary aspect, like any structural feature. The key or starting point for designing a structure is the Purpose, Command, and Hierarchy, which is all about balancing the cost of storing and moving goods and services of the focal organisation from its supplier to customer.

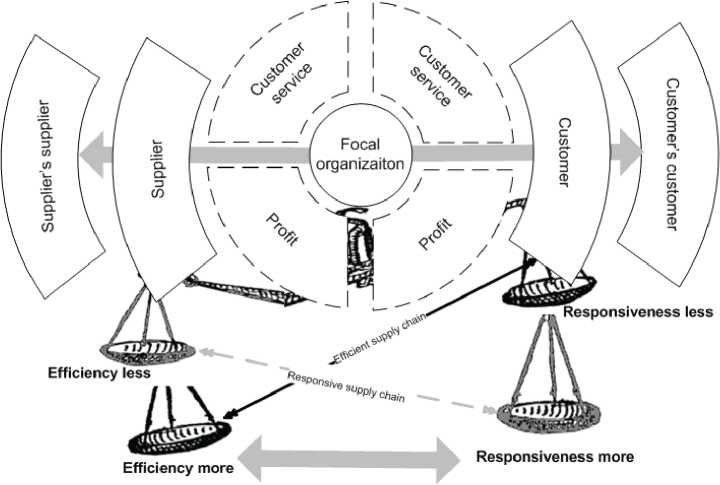

In the process, another important aspect that needs attention is customer service. Hence, the supply chain horison extends from efficiency on one side to responsiveness on the other side. Many times, these two are extremes and mutually exclusive options. Managerial challenges have brought both extremes close so that a high degree of efficiency and responsiveness is achieved, giving a competitive advantage to the focal organisation.

There needs to be a formula or framework which would prescribe the right balance. The optimal supply chain structure differs from company to company and among product and market groups. This is mainly because each product and market group is unique, and the company’s competitive approach would vary based on the resources it commands and other strategic factors like focus and vision. Some factors influence supply chain structural features –

- Character and type of product

- Nature, type, and size of market

- Distribution channel strategy

- Facilities locations and options available

- Customer characteristics and preferences

- Tax including direct and indirect taxes and levies

- Strength of logistics services and intermediary options

- Strength of information and communication channels

- Level of industry maturity and scope for innovations

2. Efficiency vs. Responsiveness

Efficiency refers to output to input ratio. In such a supply chain, the output needs to be defined in terms of revenue realised from a customer on a product or service. Every player, from supplier to channel partner of the nodal organisation, is involved in revenue generation from the customer. All these agents aim to maximise the revenue in different stages, which may be passed on to the customer. There could be conflicts in revenue maximisation objectives if any of the agents are short-focused and look at optimisation at one stage without the ability to pass it on to the customer. This is where market dynamics work to correct such tendencies. Resources deployed are the critical inputs in any function in such chain activity. Resources could be people in the form of warehouse operators, transport operators, planning specialists, and inventory analysts, so on. The resource could be time involved and functional value. All these involve certain money equivalents, which are mapped as costs. Efficiency is defined as the ratio of expenses to revenue or profit generated. Measuring income as a portion of the price realised from customers and profit is difficult.

According to Fischer I Marshall1 (1997), the primary goal of the efficient supply chain is to serve demand at the lowest cost. Hence, the efficient supply chain is cost-focused. Typically, this is common regarding necessities, utilities, and standard products. The product market would be matured, and goods or services would generally be commoditised. Examples of such product categories would include food items, dairy products, popular models of functional consumer product segments, automobiles, etc. The other key parameter of the efficient supply chain is that product design and facilities management would be designed toward cost minimisation. Higher utilisation of facilities and effective product design with standard usage and functionality for the customer will likely be key focus points for an efficient supply chain. The product design focus would be on essential functionality and added features that would not significantly add up to the cost but would improve customer satisfaction.

Similarly, the inventory level would be cost-focused, which means that nodal organisation would reduce inventory whether facilities minimisation and inventory reduction can go together if one is looking at only standard and matured product/services market. Another aspect, namely lead time reduction, would also be part of an efficient supply chain. Lead time reduction would help inventory reduction and so on. However, lead time reduction as efficiency in the supply chain is challenging as it could impact responsiveness in terms of customer service level. Thus, an efficient supply chain is one end of the supply chain structure spectrum, which works well for demand items with more certainty, low to medium value items standardised in a matured market.

Responsiveness is a measure of the speed of reaction to customer demand. It is measured as a unit of time in normal parlance, and some authors include rightfully the level of customer service. That is, if demand for a product is 100, the level of service measures the percentage of orders served. There could be different measures like fulfillment to demand, fulfillment to promise, and complete fulfillment, which will be discussed in the chapter on Performance Measurement. In simple terms, responsiveness is speed and level of customer service.

According to Fischer, I Marshall2 (1997), the primary goal of a responsive supply chain is to respond quickly to demand. Apart from the quick response, one may also consider the ability to serve demand as a factor. It may be accounted for in time to respond. But there are many instances apart from time, customer service level could be an important factor. Hence, a responsive supply chain is time and level of service level to customer demand. Typically, this is common in the case of high-value items, fashion goods, personalised demand items where customisation is needed, and new products at the introduction and early growth stages of the product life cycle. The product market would be in the early stages, and recent developments and goods or services would be specific to groups or individuals. For example, high engine power and modern motorcycles focused on the youth segment in India, which is high priced. Examples of such product categories would include hi-tech goods, medical equipment, garments, fashion jewelry, mobiles, electronic goods, home furniture, and selected automobile segments in passenger cars, commercial vehicles, two-wheelers, agriculture equipment, including tractors, and so on. The other key parameter of the responsive supply chain is that product design and facilities management would be configured towards creating modularity, allowing postponement of product completion. Modularity enables product differentiation and a high degree of customisation. It may require more common items but allows variety on completion.

Higher flexibility in manufacturing, allowing for meeting uncertainty in demand and accommodating a variety of product variations based on demand, would be the key manufacturing strategy for a responsive supply chain. Supplier relationship management would be driven based on the ability to respond quickly to demand variation, provide flexibility in manufacturing, and have the ability to do concurrent engineering. Quality management is a key aspect that is more than the threshold requirement for a responsive supply chain. Similarly, an inventory strategy would be focused on creating a buffer to meet service level and enable quick response to demand. This also helps for meeting demand and supply uncertainty, allowing demand flexibility. One may question whether facilities’ flexibility and inventory buffering would result in high investment and commitment of resources. Such concerns are genuine for any supply chain manager, and this has to be supported by a functional strategy of effective pricing and high margins. When one discusses high margins again, absolute and relative margins must be considered. Absolute margins refer to the gross margin in currency compared to standard items. Relative margins would look in terms of net margins compared as a percentage of the cost of production or offering of service. Often, responsive supply chains have pressure on relative margins, especially during a downtrend in the economic cycle where across-the-board sentiments are weak.

Another aspect, namely the lead time reduction irrespective of cost, would also be part of a responsive supply chain. This sounds theoretical and contradicts the right management perspective. How can one recommend lead time reduction irrespective of cost? To understand this, one has to interpret this concerning customer service level and the relationship between increasing service level or availability vis-a-vis cost of providing the same. After a point, increasing responsiveness would require more than a proportionate cost increase and affect the margin. However, contemporary manufacturing management practices are addressing this issue with new techniques like JIT, lean, and so on, which will be discussed in later chapters.

Thus, a responsive supply chain is on another end of the supply chain structure spectrum, which works well for demand items that have uncertain characteristics, especially for high-value items, new products with more certainty, products that lend for customisation, and market being in early stages of growth stage in the product life cycle and or innovation is the essential character of the product group like electronics and medical equipment.

3. Boundary for Efficient and Responsive Supply Chain

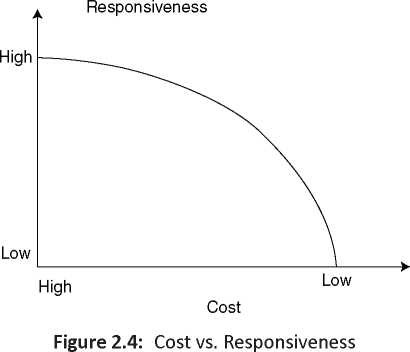

Efficiency is a measure of cost. Supply chain efficiency would focus on reducing cost, customer service level, response time, etc. As mentioned earlier, efficiency would focus on fewer variants and standardisation of products and manufacturing setup. Hence, efficiency leads to responsiveness. On the other hand, responsiveness is the speed at which one services customer requirements. Such a speed can often be achieved with higher inventory, expensive and reliable movement, etc. A responsive supply chain would mean increased costs. Thus, a direct relationship exists between responsiveness and efficiency.

Ideally, any supply chain manager would like to reverse the relationship, which is a challenge in supply chain management. The objective of cost minimisation and increased customer service is what a manager would look forward to. Beyond a point for a small proportionate increase in responsiveness, there is a need to spend a higher proportion of the cost, and it becomes less attractive after a point. When a firm focuses on increasing responsiveness, it must question the ability to pass such disproportionate costs to customers. Different firms approach differently based on their strategic focus and resource capability.

With low-cost electronics manufacturing shifting to China, Singapore has moved into high-value-adding activities like product design and high-end manufacturing. Whether an MNC with regional production or a regional SME, responsiveness in the supply chain is becoming key for firms in Singapore to be competitive. Thus, specific markets focus on responsive supply chains, whereas in other markets for the same category, customers would prefer to be served by an efficient supply chain. For example, a conglomerate like Hindustan Unilever Limited would have a different focus in structuring based on whether it is a personal care product segment, home care, food, hygiene products, or dairy products like ice creams. It needs to structure an efficient supply chain for most of the segments in which it operates. However, it has to balance with responsiveness as market share depends upon the ability to service customers. Hence, the supply chain managers and system have the pressure to balance both efficiency and responsiveness. For example, personal care products need to be contemporary, and the ability to introduce new products to attract customers is important. In contrast, a popular body wash soap segment needs to be cost-efficient.

On the other hand, products like sugar manufacturing and marketing will have cost-efficient configurations. Similarly, paper and pulp manufacture would be cost-efficiency driven. Products like the manufacture of cycles and popular two-wheeler models would be efficient with less flexibility as manufacture and marketing would be based on demand estimates.

Product groups like tractors, commercial vehicles, middle and high-end car segments, electronic goods for mass consumption, and so on would adopt a somewhat responsive supply chain. This is mainly because the price is higher, and product demand may change quickly based on environmental or external factors. Finally, responsive supply chains would be high-tech items like smart watches, mobile phones, medical equipment, fashion goods like apparel, jewelry, and premium automobiles. Demand forecasts are complex, and customers are not primarily concerned with the price compared to the product’s possession value.

The responsiveness and efficiency spectrum are two ends of the supply chain spectrum. The supply chain strategy would be understanding the positioning and structuring the supply chain network accordingly. Industry structure, competitive conditions, and the behaviour of firms decide the evolutionary trend. As one may notice, many situations vary from industry to industry, from firm to firm within an industry, from Market to Market for a firm, and within product categories or groups. The challenge is managing this dichotomy of cost vs. responsiveness, which would run through all managerial aspects of the supply chain while satisfying customer demand. Decisions concerning supply chain perspectives like inventory management, transportation, facilities management, sourcing, pricing, and information management are twined around the choice of efficiency and responsiveness as the purpose of the supply chain network.

4. Push-Based Supply Chain

One of the broad classifications of a supply chain is a push-and-pull-based supply chain based on a process view. A prima facie pull-based supply chain relates to responsiveness, whereas a push-based supply chain is associated with a cost-efficient supply chain. Both push- and pull-based supply chains are seen as strategies and approaches to supply chain configuration, whereas cost efficiency and responsiveness are more like the purpose and philosophy of a supply chain network.

Push-based supply chains, in simple terms, work in anticipation of customer orders. It is seen as a speculative supply chain because it is engaged in anticipation of customer orders. One needs to understand the following issues while analysing a push-based supply chain –

- Why should a manufacturer prefer to set up his production function and incur huge marketing and sales support to woo customers?

- Do inherent product, market, and industry characteristics warrant push strategies?

- Are there certain processes or structural features that facilitate only push strategies?

- What is the relationship between cost efficiency and responsiveness if push strategies are to be pursued?

- What are the managerial levers available to make push effective and cost-efficient?

It is evident from above that aspects of business require push strategies in the supply chain to be deployed. The management must ensure that it applies all its efforts and resources to achieve the cost minimisation objective when there is a need for certainty in demand. Over the years, business and industry evolution has facilitated streamlining approaches towards cost-efficient push-based supply chain strategies. These strategies are to be well executed with planning and operations management. Multi-disciplinary orientation is important for successful implementation. It is important to understand the drivers for success for cost efficiency. Imagine situations where there is a wrong approach or implementation practice. Then, it would lead to the failure of the supply chain network and numerous organisations’ networks in the process, mainly affecting the nodal organisation.

5. Key Conditions Enabling Push-Based Supply Chain

The enablers of push-based supply could be due to industry factors, organisation of distribution structure, nature of the product, the strength of support services, including logistics service providers, etc. These are the aspects the first three questions raised earlier relate to.

Characteristics Influencing Push-Based Supply Chain Structure

|

Features |

Example | Focus |

Remarks |

| Character and type of product | Steel | Efficiency | Standardised products are used as raw materials for many goods. |

| Nature and Size of Market | Perishable markets like fruits and vegetables | Efficiency | The definite time frame for market reach and life of the product. Must be sensitive to demand |

| Global market | Efficient | Products in the global market may adopt an efficient supply chain using multiple plant locations and distribution centers. | |

| Distribution channel strategy | FMCG goods like personal care products, beverages, and so on with more intermediaries | Efficiency | More intermediaries, larger inventory across the chain, and need to be cost-centric. |

| Facilities locations | Centralised facilities like Amazon | Efficient | Time to service could be longer, but cost efficiency would be the focus. |

| Customer characteristics and preferences | Standard product choice and price sensitive | Efficiency | Staple food items and necessary goods. |

| Strength of logistics services and intermediary options | Matured LSP who can handle DCs and transportation, especially for manufacturing standard products | Efficiency | As in the case of bulk chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and the engineering industry, make-to-stock is practiced. |

| Strength of information and communication channels | Structured information and communication channel | Efficient | Supportive systems for planning and distribution management. This would apply to the industries mentioned above as well. |

| Level of industry maturity and scope for innovations | Matured industry situations – Popular two wheeler segment in India | Efficiency | As the industry matures, there will be stable growth and cost competitiveness. |

One of the key enablers of the push strategy is the manufacturing strategy of ‘Made-to-Stock (MTS)”. MTS strategy is one where a product is produced to stock to meet expected or estimated demand. Based on experience, a production plan is drawn so that a sales order might come in, and delivery to the customer is done from the existing stock. One may appreciate that the MTS strategy would work where lot sizes would require production in large lots, and releases must be made in batches. Manufacturing setup would demand such kind of runs wherein production function is constrained by lumping into some standard size of operation. Second, continuous process operations like chemicals, cement, sugar, and similar bulk products could run again based on operating efficiency rather than on-demand requirements. Manufacture of such products would be driven by production economies and capital machinery setup, which would have considered specific demand patterns. There are situations wherein it may not be a demand pattern but a supply of raw materials determining the MTS

Disclaimer: The content/information published on the website is only for general information of the user and shall not be construed as legal advice. While the Taxmann has exercised reasonable efforts to ensure the veracity of information/content published, Taxmann shall be under no liability in any manner whatsoever for incorrect information, if any.

Taxmann Publications has a dedicated in-house Research & Editorial Team. This team consists of a team of Chartered Accountants, Company Secretaries, and Lawyers. This team works under the guidance and supervision of editor-in-chief Mr Rakesh Bhargava.

The Research and Editorial Team is responsible for developing reliable and accurate content for the readers. The team follows the six-sigma approach to achieve the benchmark of zero error in its publications and research platforms. The team ensures that the following publication guidelines are thoroughly followed while developing the content:

- The statutory material is obtained only from the authorized and reliable sources

- All the latest developments in the judicial and legislative fields are covered

- Prepare the analytical write-ups on current, controversial, and important issues to help the readers to understand the concept and its implications

- Every content published by Taxmann is complete, accurate and lucid

- All evidence-based statements are supported with proper reference to Section, Circular No., Notification No. or citations

- The golden rules of grammar, style and consistency are thoroughly followed

- Font and size that’s easy to read and remain consistent across all imprint and digital publications are applied

CA | CS | CMA

CA | CS | CMA